Opening scenes or first pages are usually some of the most interesting parts of movies or books. Especially upon second viewing/reading, expository scenes reveal a lot of information to prime us for a narrative's main themes and characters. Most often, they basically contain the central conflict of the story.

Sergio Leone - like Kurosawa whose YOJIMBO (1961) he shamelessly remade as A FISTFUL OF DOLLARS in 1964 - was fond of very long takes and elaborate tracking shots which he contrasted with frenetic cutting in action scenes.

The Triangular Composition

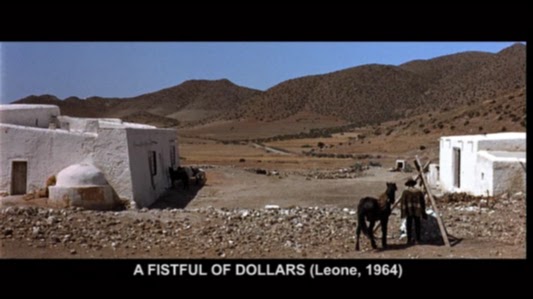

After a rotoscoped credits sequence, his first Italian western fades in on a low angle shot of rocky desert sand. Before we see the "man with no name" (actually called "Joe" in this one), we see the hooves of his mule. The small size of the animal is immediately recognized because the rider's feet are dangling very close to the ground.

The camera then pans up and slowly trucks in to reveal the back of a man wearing a poncho. Remember, this is Clint Eastwood's first appearance in Italy and his first in a theatrical western at all. And at that time, nobody expected the star to be stubbly and dirty. This first shot continues until the following composition is achieved:

The basic conflict is visualized in this single composition: two warring parties live across the road from each other, Eastwood "smack in the middle" checking them out before playing them off against each other. Him standing closer to the right house may be simply a matter of balancing the composition. However, we will eventually learn that morally he is closer to the people living in the right house.

In form and content, all three films are based on triangles. Aside from the visual triangle that is formed between the two houses and Eastwood (and his mule), the well is also constructed in a triangular shape.

Then Leone cuts to a reverse medium close-up of Eastwood drinking and observing. I will not go into any more detail about the rest of the opening scene that basically sets up the iconic "man with no name" as a stoic western version of Mifune's unkempt animal-like YOJIMBO character Sanjuro.

The Man With A Rifle

Moving on to the very first shot of FOR A FEW DOLLARS MORE (1965), we can see how Leone started to get more confident with the vast widescreen of the Techniscope frame (a non-anamorphic grainy version of Cinemascope).

After a title card reading "Where life had no value, death sometimes had its price. That is why the bounty killers appeared." the film opens on a blinking point of light that is reminiscent of the white burnout at the end of the first films credit sequence:

But upon closer examination, this blinking point guides our attention to the only spot of interest in the otherwise empty long shot of a gritty desert location. We already look at the middle of the frame when a far off rider appears during the dissolve.

Supported by the artificial representation of spatial acoustics on Italian soundtracks, the whistling and gun loading may very well emanate from the rider in the distance. In fact, even in 35mm the grain will not allow the audience to read the silhouette clearly. It is not even clear if the rider in the distance sits on a horse or a mule.

|

| These compositions are obviously made for theatrical exhibition and not for cellphone screens. |

From all we know from the first film and the posters, this might be Clint Eastwood approaching. But then (0:55) the sound is clearly located offscreen since we see smoke and hear a gunshot after which the rider falls off in the distance. But who are these two people? To make matters worse (in a film that first came out with all the voices dubbed by Italian actors), the offscreen humming and whistling was reportedly done by Sergio Leone himself.

This rigid long take sets up several key aspects of the following film: we shared the point of view of a sniper. In a traditional western this must be the villain because no honorable western hero ambushes another man. But with this film Leone introduced the bounty killer as a professional and thus motivated a whole sub-genre of bounty hunter westerns.

From the whistling it becomes clear how emotionless the bounty-hunting business is executed. We also see an action while the director withholds vital information to the scene - in this case the identity of killer and victim. Of course, everybody knew from the advertisements, that this time Eastwood was supposed to be meeting his match in the person of a man in black. With FOR A FEW DOLLARS MORE Leone introduced his fragmented flashback technique that was unheard of in western storytelling.

The cynic key to successful bounty-hunting lies in the choice of weapons as Lee Van Cleef's character Col. Mortimer proves a line of dialogue from FISTFUL OF DOLLARS: "When a man with a .45 meets a man with a rifle, you said, the man with a pistol's a dead man"

Mortimer usually kills with a long-range rifle just from outside his opponents shooting radius.

Going The Distance

By the time he did his internationally funded masterpiece THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE UGLY (1966), Leone had perfected his directing style to the point where he was able to successfully defy all conventions, be they visual or content-wise.

Ever since FISTFUL OF DOLLARS it has become one of his trademarks to cut from extreme long shots to close-ups without cushioning medium range shots inbetween. The camera framed the actors' faces increasingly closer until there was barely more to see than the actors' eyes (the now famous "Italian shot").

THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE UGLY was again based on the concept of three (visual triangles galore) but also on the concept of surprise. There is hardly a scene that is no built around a surprise revelation. Moreover, the concept of withholding information is not only central to the narrative, it is also central to the visual realization. This leads to a highly stylized setting that does not extend beyond the frame edges.

Even the few suspense scenes (the natural opposite of surprises) turn out to be achieved by a visual trick that is revealed in a surprise ending.

So with these two concepts (juxtaposing extremes and withholding information) in mind, the first two shots of THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE UGLY constitute one of my favorite opening scenes:

Then we get the reverse shot. We share the point of view of this gnarly character. Now the searching for information begins. What is he looking at?

Is it the dog that crosses the plain? (The dog appears again hours later to momentarily consternate a frenetic Tuco).

No, there are two specs approaching from the distance. Leone cuts back to Al Mulloch, then back to the approaching silhouettes on horsebacks. Will they have a stand-off? Will he shoot the two with a rifle? We haven't seen anything else than his face, so he might as well carry a long-range rifle.

Of course, the situation turns out to be a wholly different one.

After opening ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST with a few short close-ups, Leone came back to the FISTFUL OF DOLLARS approach in his Mexican revolution western GIU LA TESTA (DUCK YOU SUCKER, 1971) with a long take that fades in on a close-up followed by a tracking shot into the establishing composition.

Note: all screenshot and excerpts from THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE UGLY have been taken from the impeccable Italian restoration (IL BUONO, IL BRUTTO, IL CATTIVO) (un)available on Blu ray which is visually far superior to the American one but unfortunately does not contain the English language soundtrack.