French author Pierre Lambert once again publishes a ridiculously expensive art book that is worth every cent. Although in numbers there may be less artwork on display here compared to the usual “Art of” book, but with so many production backgrounds reproduced in the most astonishing print quality, Lambert’s large format volume about Walt’s last feature The Jungle Book is nothing less than marvelous.

The Art Of Animated Features

Nowadays, “Art of” books accompany the release of almost every American animated feature. More often than not, those books simply seem to remind us how much individual style had to be suppressed to come up with widely acceptable mainstream aesthetics. The historical information these books provide seldom goes beyond self-congratulatory making-of stories common in DVD special features, which looks less embarrassing printed on glossy paper.

One gets the impression that, according to these books, the “art” of animated films is based on “unique” superficial styles (later considerably toned down for the finished film), focussing on design rather than on animation. Without wanting to sound too conservative, in the case of the features made during

Walt Disney’s lifetime, most often I actually like what ends up on the screen and not just the preliminary artwork. Already back then, the mantra that you couldn’t get too graphic in a feature without losing character believability was repeated over and over, but even the blandest character designs came to life through animation.

Before the 1990s, “behind-the-scenes” material was only available in a few Disney endorsed books, especially the luxuriously illustrated but heavily biased ones by

Frank Thomas and

Ollie Johnston. Meanwhile there are lots of wonderful Disney endorsed books by historians like

John Canemaker and

Brian Sibley that are full of preliminary art and lavish color plates. On the other hand, such indispensable independent books as

Didier Ghez’s self-published interview collections or

Michael Barrier’s thoroughly researched works cannot rely on the same wealth of artwork.

The Art Of Making Art Books

There is a third way, though: French author

Pierre Lambert’s way. What makes

Lambert’s independently published books so unique is their dignified presentation and the amazing print quality of his handpicked reproductions (backgrounds with cel overlays are even printed on gleaming paper to simulate real cel overlays). Currently, there is nothing comparable on the market.

I first heard of

Pierre Lambert in 1997 when his lavish

"Pinocchio" book was released in English and reviewed on German television. I wasn’t too familiar with the internet back then and without a credit card I wasn't able to order the book through

amazon.com. Later on, when I finally figured out how to get it, it was already out of print.

So when I heard about

Lambert’s new release

"Le Livre De La Jungle" (The Jungle Book), I knew I had to get it immediately at all costs, since

The Jungle Book has always been my favorite Disney movie and I’ve been waiting for such a book for what seemed like centuries.

Most books that deal with Disney studio history in general do not devote more than a few paragraphs to Walt’s last feature, most often dismissing it as below average but extremely popular with audiences.

On a side note: the most interesting background information so far can be found in the special features DVD of the

platinum edition that presents many previously unpublished storyboards and other preliminary sketches. The highlight for me was the collection of abandoned

Terry Gilkyson demo recordings and a more

Beatles-inspired demo of “That’s what friends are for”.

Kipling, Peet, Disney – Three Opposing Forces

But back to the book.

Pierre Lambert’s French text is a little gem all by itself (sometimes it comes in handy that in Switzerland you’re forced to learn French in school). Even though there is no newly acquired information (all the interviews have already been published elsewhere), this is the first time all these sources have been put together so neatly.

Lambert starts with

Bill Peet's recollections of the project’s origins and then compares

Kipling’s, Peet’s and

Disney’s version of the story. For every crew member he introduces he seamlessly incorporates a short but very insightful biographical overview, largely focussing on the people whose contributions finally made it to the screen.

While

Lambert obviously writes from an admirer’s point of view, he never feels the urge to gloss over ruptures and studio mythology incompatibilities. He adresses re-use and questions the “time-saving” part of this strategy by quoting

John Ewing about having to redraw a chase sequence from

Mr. Toad. As

The Jungle Book is much more character than story driven,

Lambert structures his text around the development of the characters.

The Selected Artwork

One can only dream about what film this would have been had

Peet, Peregoy and

Gilkyson got their way. But while not suppressing any evidence of different versions

Pierre Lambert focuses on the artwork of the film that finally got made. Mostly production artwork - animation art, that is.

After about twenty pages of text the artwork is presented in the order of the events in the film. While sketches by

Ken Anderson and

Al Dempster as well as a lot of uncredited works are present, most of the book is filled with gorgeous background paintings (sometimes with cels and overlays) and animation drawings. The only non directing animators featured are

Eric Larson (vultures) and

Eric Cleworth (elephants).

I don’t know how much of

Walt Peregoy’s original concept art is still buried somewhere in the ARL or if he has taken it with him when he left the studio in 1965, but at least there is one painting of the man village credited to him in the book (page 217).

Compared to the strange

Jungle Book selection in

(John Lasseter’s ?) “Archive Series: Animation” the selected animation drawings here - from the loosest

Ollie Johnston drawing of Mowgli hugging Baloo to

Frank Thomas’ solid King Louie - really do justice to their creators.

The same cannot be said of many of the reproduced cels, though. Hardly any of the selected (available?) original production cels are key frames. While it is desirable to have setups that differ from the familiar ones, not every inbetween is a great drawing (which is ok in motion).

The Trouble With Cels

The Trouble With Cels

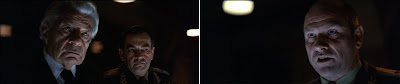

That’s also where the process of reproduction reveals its only flaw: cels and overlays look like they have been photographed/scanned in front of a white background, then digitally rotoscoped/cut-out and overlaid over the production backgrounds. Sometimes the white edges show, sometimes the pencil outlines are cut fuzzily. Also some of the multiplane overlays and imitated special effects don’t work very well, as is the case in some Shere Kahn cels with grass overlays (page 197) that originally looked slightly translucent (like in the screenshot on the left).

In order not to gray down the backgrounds that are the main attractions, this process is understandable and thus acceptable. What is not, in my opinion, is that some of the cels are wrongly adjusted or even in front of the wrong backgrounds, like the one on the cover. Why would anyone want to do that? These layouts may not have been planned to be seen in their entirety but they certainly have been planned with character positions in mind.

cover setup (2009) vs. story book setup (1982)

vs. screenshot (Platinum Edition, cropped at 1:1.75)

I have another minor quibble though: I was a little disappointed that apart from one or two preliminary backgrounds attributed to

Al Dempster, there are no background or layout credits at all. I guess there’s no way to find them out as there seem to be no background drafts, but if someone knows, I’d be glad to put a reference list together.

Already A Personal Favorite

One of my personal discoveries was how much of the character designs is still present in

Bill Peet story sketches, although he left the studio before

Walt commissioned the re-write by

Clemmons, Wright and

Gerry and remains completely uncredited. There are sketches of Kaa and Shere Kahn that really put

Ken Anderson’s and

Milt Kahl’s contribution in context. While

Bill Peet was vengeful about

Tytla getting credits for

Dumbo animation

Peet thought was already present in “his” storyboards,

Kahl has made the two characters so much stronger by just a few alterations

(Peet’s version of Kaa resembles the one in the beginning at night and not the later daytime design).

All points of criticism aside, this is already one of my most beloved Disney books ever. Get it while you can, even if you don’t speak French, because it’s the reproduced artwork that makes this book special. There are already rumors that there may be an English version sometime soon.

All screenshots from The Jungle Book Platinum 2-Disc Edition DVD.